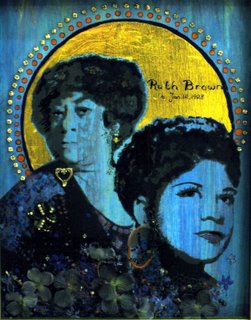

R& B's Tireless Voice

Ruth Brown Made Hits And Made Sure Artists Got The Money They Deserved

By Richard HarringtonWashington Post Staff WriterSaturday, November 18, 2006; Page C01

She'll always be Miss Rhythm, the powerhouse belter of those 1950s blues hits that made Atlantic Records.

Ruth Brown could swagger on "Teardrops From My Eyes" and turn imperious on "(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean," its very first word rising like a squealed exclamation point. There was a world of hurt in those songs and an insistence on some justice, a boldness of voice that Miss Rhythm reached for as Miss Righteous, the crusader who forced the record industry to pay her fellow artists the royalties they had never received.

Ruth Brown Made Hits And Made Sure Artists Got The Money They Deserved

By Richard HarringtonWashington Post Staff WriterSaturday, November 18, 2006; Page C01

She'll always be Miss Rhythm, the powerhouse belter of those 1950s blues hits that made Atlantic Records.

Ruth Brown could swagger on "Teardrops From My Eyes" and turn imperious on "(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean," its very first word rising like a squealed exclamation point. There was a world of hurt in those songs and an insistence on some justice, a boldness of voice that Miss Rhythm reached for as Miss Righteous, the crusader who forced the record industry to pay her fellow artists the royalties they had never received.

Brown, who died yesterday at 78 after having been in a coma in a Las Vegas hospital for almost three weeks, was a pioneer of rhythm and blues. Even her initials bore testimony to that. Blessed with jubilance, sass and high spirits, and wonderfully expressive features that simply broadened over time, she influenced such greats as Etta James, Stevie Wonder, Bette Midler, Aretha Franklin and Bonnie Raitt.

In the mid-'80s, Brown came often to Washington, as engaging a lobbyist as you could ever find, determined to persuade Capitol Hill lawmakers and music writers at influential newspapers to shine a light on suspect practices. Whether you were a politician or a reporter, Brown didn't just buttonhole you. She'd lean into you, working at close quarters, poking important points one at a time into your arm or chest, as if her truths would only become self-evident through tactile confirmation. In hearings, she would shake in indignation, that voice rising and falling, and congressmen were mesmerized. Reps. Mickey Leland and John Conyers professed their complete infatuation; even Sen. Jesse Helms voiced his support, saying, "The record for me was '5-10-15 Hours.' "

She gave the best hugs in the business, even in print. In her 1999 autobiography, she credited my extensive Post coverage with pressuring Atlantic to readdress royalties, then continued to bend my ear about the plight of her fellow hitmakers of the '40s, '50s and '60s. For Ruth Brown, it was unfinished business as long as every label wasn't onboard the royalty reform train.

Raitt, who inducted Brown into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, yesterday praised "her genuine caring about trying to get [veteran artists] justice, not charity." A close friend and frequent duet partner, Raitt called Brown "the preeminent R&B queen and diva we all appreciated and looked to -- in that world, there's only one Ruth Brown."

Little Richard said much the same at one of Brown's last performances, at the end of September at the San Francisco Blues Festival. Bringing her back onstage for a duet, he credited Brown's squeals, records and style with being a major influence.

By the time Brown was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame -- on her 65th birthday! -- the singer was a decade into her crusade for royalty reform, centering on royalties from her Atlantic tenure as well as earnings from CD reissues, best-ofs and anthologies, all of which made money for the label but none for Brown. Howell Begle, a communications and entertainment lawyer and ardent R&B fan, made Brown's cause a personal crusade, working pro bono on her behalf and signing up several other former Atlantic artists, including the Coasters, the Drifters and Big Joe Turner.

In 1988, as part of its much-covered 40th-anniversary celebration, the label announced it had wiped out past "debts" and made lump-sum payments of retroactive royalties for 35 acts; Brown's $30,000 check was her first from Atlantic in more than 20 years. Atlantic also ponied up $2 million to launch then-Washington-based Rhythm and Blues Foundation, where Brown remained a trustee, fighting the fight with as much determination as when she'd begun it.

Sam Moore, of Sam & Dave, a beneficiary of her royalty battles, said Brown "would never bite her tongue when it came to sticking up for the rights she believed we were all due. She was a loyal friend.

"And if you ever saw her on a stage, she owned it," Moore said from Japan, where he was touring. "Even with numerous health issues, if you saw her perform, you'd never ever sense there was anything wrong."

A few years ago, Brown had a devastating stroke and couldn't walk or talk. After more than a year of physical and vocal therapy, she was back onstage, her only concession being that she performed sitting down. A gifted interpreter able to deliver gorgeous ballads as well as her trademark bawdy blues, Brown could also tell jokes about friends like Ray Charles, whose very first band was actually Brown's touring band. Still, he apparently scoffed at Brown's suggestion that Halle Berry play her in the film "Ray." According to Brown, Charles said, "I may be blind, Ruth, but I'm not that blind!"

Brown didn't get much airplay anymore, except on oldies stations. Yet a 50-year-old hit was all over television this year when "This Little Girl's Gone Rockin'," written especially for her by Bobby Darin, popped up in a Hummer H3 commercial and seemed as fresh as any modern hit.

But the song that defined her life and stayed in her repertoire 60 years was the one that helped her win first prize at 15 at the Apollo Theatre's fabled Amateur Night: "It Could Happen to You," a Johnny Burke/Jimmy Van Heusen standard. The song's interpretation would change for her over the decades, particularly the lovelorn ballad's counsel to "Hide your heart from sight / Lock your dreams at night / It could happen to you / Don't count stars, or you might stumble / Someone drops a sigh, and down you'll tumble."

Tumbles there would be, many of them cruel and capricious, yet Brown survived, standing up for herself, her music, and the rights, royalties and dignity of her peers.

No comments:

Post a Comment